Exploring the art is seeing the world not only through the eyes of the artist, but also through the eyes of their dogs! EQUALS is collecting the most notable pieces of art as well as artists stories with a humble goal to show how much love and affection artists have between them and their dogs, and so does every person who is serious about their relationships.

Pablo Picasso

Lump, the Dachshund, met Picasso, the artist, on April 19 in 1957 for a lunch at “La Californie”, Picasso’s hillside mansion in Cannes, France. It was like a love affair. Picasso had many dogs, but Lump was the only one he took in his arms. Picasso even painted a dinner plate specially for Lump and would feed him from his hand. There is even a book: “Lump: The Dog Who Ate a Picasso”, relating to the time when Picasso drew a rabbit on a sugar-impregnated cake-box and cut it out. Lump couldn’t resist, seizing the sugared cardboard rabbit (which would have been worth tens of thousands of euros if it had survived) and ate it. It seems clear that Lump had a taste for Cubism.

In fact, Picasso’s life was full of dogs. He had many, of many different breeds, including terriers, Poodles, a Boxer, Dachshunds, a German Shepherd, Afghan Hounds, and numerous “random bred” dogs. Many of these were “borrowed” or “stolen” from friends and associates in the same way that many of his women were. The dogs were as much a part of his life as his female companions, and they went everywhere with him. He also gave dogs to his friends as gifts, in part to ensure that he would never be in their company without a dog. When his various relationships broke up, Picasso would often leave all of his goods behind him and go off to live in a new place with a new woman. Usually, he would only arrange to have a few things returned to him, including some of his recent paintings, some of his brushes and paint, and his dog or dogs. The rest was all left to friends or to the woman whom he was leaving. One of the most important dogs for Picasso was Lump.

Francisco Goya

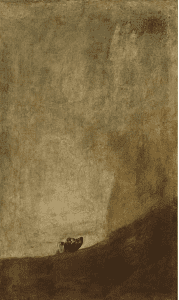

In 1819, Goya purchased a house named “Quinta del Sordo” (“Villa of the Deaf Man”) on the banks of the Manzanares near Madrid. It was a small two-story house which was named after a previous occupant who had been deaf, though Goya also happened to be functionally deaf, as a result of an illness he had contracted (probably lead poisoning) in 1792. Between 1819 and 1823, when he moved to Bordeaux, Goya produced a series of 14 works, which he painted with oils directly onto the walls of the house.

At the age of 73, and having survived two life-threatening illnesses, Goya was likely to have been concerned with his own mortality, and was increasingly embittered by the conflicts that had engulfed Spain in the decade preceding his move to the Quinta del Sordo, and the developing civil strife—indeed, Goya was completing the plates that formed his series The Disasters of War during this period. Although he initially decorated the rooms of the house with more inspiring images, in time he overpainted all of them with the intense, haunting pictures known today as the Black Paintings. Uncommissioned and never meant for public display, these pictures reflect his darkening mood with their depictions of intense scenes of malevolence, conflict, and despair.

If Goya gave titles to the works he produced at the Quinta del Sordo he never revealed what they were; the names by which they are now known were assigned by others after his death, and this painting is often identified by variations on the common title: A Dog, Head of a Dog, The Buried Dog, The Half-Drowned Dog, The Half-Submerged Dog; more colloquially as “Goya’s Dog”; or by the Spanish names El Perro or Perro Semihundido.